Conditionality and Compromise: Can #YouthLead in the Pact for the Future?

Reflections on the Pact in its context, and some recent reading/resources

Approximately six weeks ago the UN held their Summit of the Future, a high-level event in New York to “forge a new international consensus on how we deliver a better present and safeguard the future”. Youth and youth issues were notably present at the Summit and in the outcome documents, yet I have delayed on writing anything about it.

This is due to the dissonance I feel about the concurrence of a much-lauded plan for a new era of global governance, with simultaneously ongoing genocidal violence in the Middle East, horrific impacts of fighting in Sudan, protracted suffering in Ukraine, and many other crises that don’t make the news. Those with the power to end this suffering right now, through dialogue, negotiation, and settlement, refuse to do this, but send their representatives to New York to talk about “a better present” and how to “safeguard the future”.

At the same time, these very crises demonstrate the fundamental failings of the current systems; so meaningful and high-level discussion and agreement on priorities and actions to address these systemic weaknesses are more needed than ever.

I write these reflections on the Summit and its resultant Pact for the Future, and implications for the YPS agenda, highly aware of this dissonance. I write with the hope that ongoing critical engagement, advocacy, and an insistence on accountability and context, moves the needle—however slowly—towards real justice, inclusion, and commitment to people not politics.

Where are the youth in the Pact for the Future?

Multilateral diplomacy is inherently messy and partial. Large show-piece events like the Summit of the Future are necessarily performative, setting out ‘visions’ and ‘agendas’ and ‘paths’. While it is tempting to dismiss this as pageantry, beneath the spectacle, fraught negotiations over a host of topics played out in the lead up to the event.

What has resulted is a 50+ page ‘Pact for the Future’. While much of it repeats the well-worn commitments to peace, security, multilateralism, human rights and so on that we are familiar with from UN events and documents, there are some important spaces in relation to those who care about young people’s inclusion and recognition. In addition to young people’s inclusion within the Pact, the outcome documents also include a Declaration on Future Generations which is about unborn generations and leaving a world for them to inherit. I am less focused on this declaration in this post, but you can read it here.

In the Pact itself, it is noteworthy that one of the five Action Areas is “Youth and Future Generations”. The broad action area of Youth and Future Generations positions young people largely as recipients of a series of commitments around delivery of health, education, rights, justice, and the ability to participate. While I am usually cautious about positionings of young people as passive, in this it is actually good in that it recognises that it is other stakeholders who have responsibilities and obligations to younger generations in the present as well as to those in the future.

Of more specific relevance to the focus of myself and this readership one of the Actions under the second area ‘International Peace and Security’ was specifically on YPS. To get this inclusion required dedicated advocacy within the UN and beyond.

The conditionality of youth inclusion (again, still)

Because of the nature of the negotiations there is a publicly available revision history of the Pact from the months and weeks leading up to the event. In Rev.1 YPS was not mentioned at all—surprising and yet unsurprising at the same time.

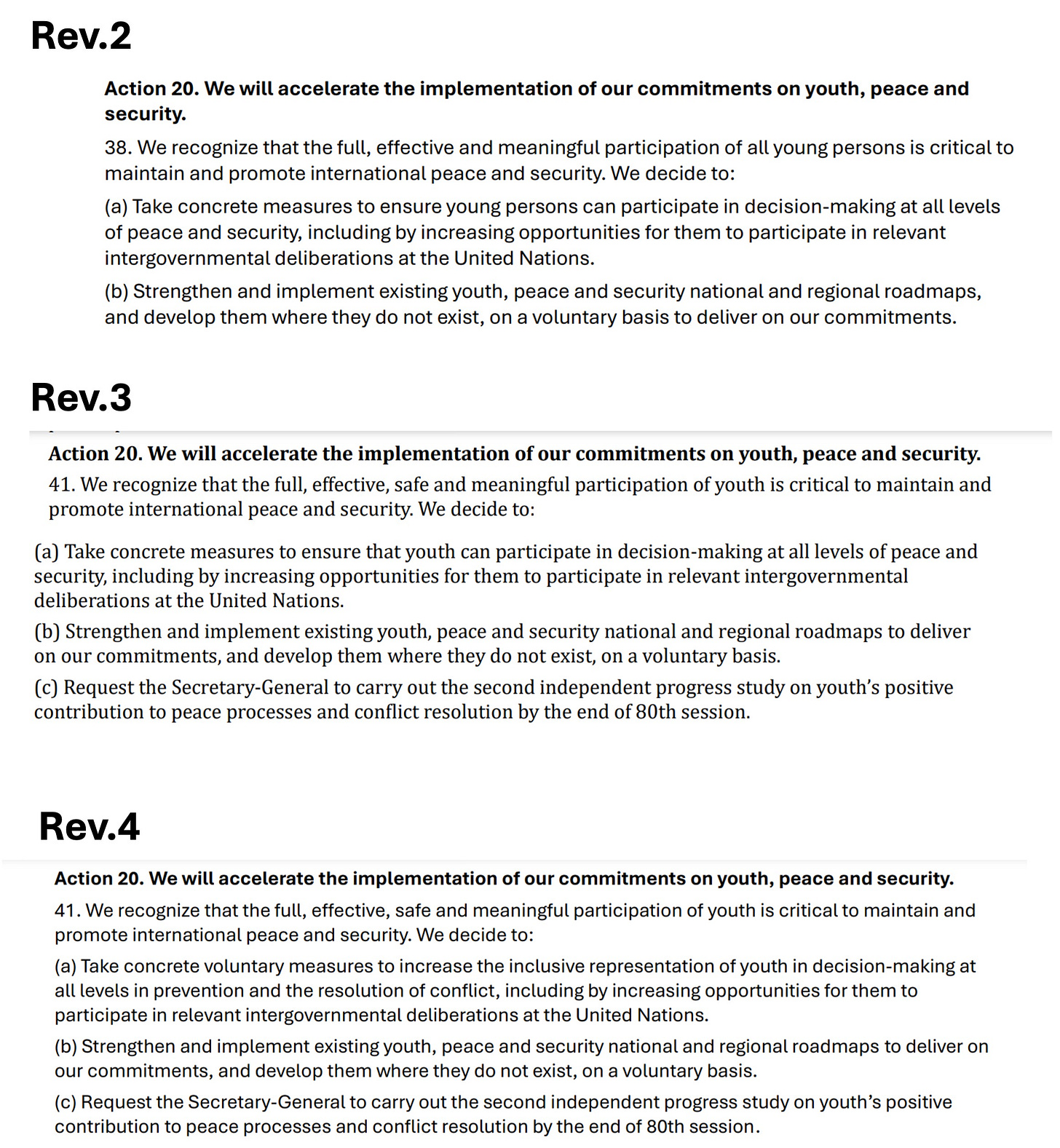

Careful lobbying saw YPS included in Rev.2, with two actions to be taken: ‘take concrete measures’ to ensure participation in decision making and ‘strengthen and implement’ existing YPS roadmaps and “develop” them where they don’t exist, on a voluntary basis. By Rev.3 Action 20 on YPS sees a third action added: to request a second independent progress study on YPS (more on this below).

However, it is Rev.4 that I find interesting because while the three actions items under Action 20 on YPS remain, the ‘concrete measures’ to ensure participation has become “to increase the inclusive representation of youth in decision-making’; however, both this and the second action are now only to be done on a voluntary basis.

The final document retains the voluntary nature of the first two actions on Action 20, and the language is unchanged from Rev.4.

General encouragement for stakeholders to essentially keep doing what they are doing, with no timeline, no resourcing, no obligation—despite the fact that the UNSC Resolutions that constitute the basis of the YPS agenda are binding on Member States—is insufficient. The fact the decision to weaken the statement on YPS actions is evident in the revision history raises questions about the political will of stakeholders to these commitments.

A Second Independent Progress Study

Amidst this politicking is the third action which is actually a concrete one. Action c) requests a second independent progress study on YPS. The timeline is tight for this, and the Pact makes no mention of how it will be funded (of course). However, this is a gain for those advocating for youth inclusion in peace and security.

Since The Missing Peace, the first independent progress study on YPS, in 2018, reviews of and updates on the agenda at the UN level have occurred through the highly politicised process of Secretary-General Reports. These were finally formalised as a requirement every two years in Resolution 2419 (2018), and there have been three (I’ve written on the 1st (2020), and 3rd (2024) previously). The difference between an SG report and an independent progress study is scope, format, and the kind of inputs that can be meaningfully accounted for.

Truly global analysis of the YPS agenda has been limited for practical and resource reasons. We continue to cite the numbers from the 2017 UNOY and SFCG report that most youth-led orgs operate on less than USD$5000/ year. Seven years on, and with a focus on financing the YPS agenda being present in the last few years, I would argue we need more up to date data on financing YPS (this isn’t to minimise the great work that many have been doing on financing in this space).

When Graeme Simpson did his study, the research was carried out through 2017 largely. YPS was still in its infancy (to use a teleological analogy ;)), and the stakes of the discussion were about raising the profile of the value of taking youths’ positive contributions and leadership seriously. Simpson offered us the conceptual frame of ‘the violence of exclusion’ to help advance our conversations. I would argue that I think we are now well aware of what exclusion does to young people; and it is time to think about not only what inclusion but leadership of youth looks like on peace and security. This is the potential of a second independent progress study.

#YOUTHLEAD, but are they taken seriously?

As we approach the first decade of YPS, I think we can set our expectations for success higher than ‘the Pact mentioned YPS’. However, I’ll take it. The inclusion of the call for a new progress study is a further concrete step.

Just as the first YPS resolution made youth participation conditional through its repeated use of “as appropriate” to describe when they should be included; the repetition of ‘voluntary’ measures and contributions specific for YPS tells me there is more work to be done on having YPS taken seriously. Illustratively, it is notable that the Action item before YPS is on WPS, and the word ‘voluntary’ does not appear in that section at all. All commitments are in absolute terms: “Deliver on our commitments”, “Take concrete steps”, “Accelerate our ongoing efforts”.

The day before the Summit in September there was a youth-focused afternoon: #YOUTHLEAD for the Future. This dedicated focus elevates the attention to youth, but as always creates a division between the space the youth leaders participate in (before, around, outside of) and the formal event itself. This is a constant tension in any institutionally led event, and a space that further work can be undertaken to bring together not only the ‘voices’ of youth but their concrete expert advice on actions.

Compromise in YPS Advocacy – new article from me in Globalizations

This is a convenient, and unplanned segue for this post to the fact that I have recently had an article published in the journal Globalizations, which is open-access and available for anyone to read. It is titled, ‘What we give up to get where we’re going’: compromise in the institutionalizing of youth peace advocacy.

This article draws on my research with advocates for the YPS agenda over the past few years. It develops the idea of compromise in youth peace advocacy to understand young people's engagement with institutional processes not as complicity or naivety, but as considered evaluated decision making about their advocacy.

For those interested in the academic argument of the piece I engage with Bourdieu's idea of the field to make visible the contestations over power and access that happen within the YPS space, and recognise youth as having agency and decision-making capacity in ways that are often overlooked.

Much of the literature on civil society participation or engagement with the institutions and practices of global governance is framed around either ideas of ‘inclusion’ or critiques of ‘co-optation’, and I hope this piece offers something for those working in other areas of civil society engagement with institutional processes to nuance these existing conversations.

Beyond academic discussions, I hope the piece might also offer something to practitioners who are wrestling with the dynamics of youth engagement, and how youth leaders grapple with the complexities of ‘coming to’ institutional spaces to advance their advocacy and peacebuilding agendas. In reading various posts from young advocates who attended the Summit for the Future on social media, I was struck by their reflections on the value of participating in these spaces and the challenges that also are present—we might think about these as the ways youth choose to compromise.

This article is part of a forthcoming special issue on the role of children and youth in global governance (beyond just peace) in Globalizations, which I strongly recommend to everyone in full once it is all available! As always I remain deeply grateful to everyone who so frankly and generously shared their experiences with me in doing this research.

Recent Reading and Resource Suggestions

There have been a number of other great resources and publications in the last couple of months. Sharing those I’ve come across here; as always, I would love to know of other resources!

The Canadian Coalition on YPS has released a fantastic toolkit Beyond Tokenism, in English and French, which offers practical tools and strategies to move beyond tokenistic participation of young people. I appreciate the clear framework, advice on how to support youth-led work, and build intergenerational parterships. The CCYPS undertook a survey and detailed research to inform it, and I think it’s a great addition to the toolkits and guidance that already exist.

Along similar lines, the United Network of Young Peacebuilders (UNOY) has published a Guide on Inclusive Youth Consultations, available in English, focusing on the dynamics of each stage of consultative processes. Helpful checklists for both youth and non-youth stakeholders provide clear guidance on how to implement the recommendations through the guide.

UNITAR has published a report “Building Peace from a Distance: An Assessment of Digital and Hybrid Learning Formats to Support the YPS Agenda”, considering best practice in using digital tools and spaces particularly around training delivery. The report includes case studies from Colombia and the Philippines and details the challenges faced in engaging in digital environments.

NORRAG has published a Policy Insight on Meaningful Youth Engagement: Time to Deliver, which includes 37 chapters from youth peacebuilders, practitioners, and academics. As the report says “despite resurgent interest in youth engagement, many young people experience youth engagement practices as shallow or performative. To advance both understanding and practice, this project asks: How can we improve meaningful youth engagement and unleash the full power of youth participation, partnership and action?”

Thanks as always for reading and engaging. Please reach out with any resources or feedback, or share this Substack with others who might be interested.