Announcing the YPS Database!

Launching an online, public resource library of documents related to the YPS agenda

I’m excited to announce the launch of the Youth Peace and Security Database (YPSDB): an online, public resource library of documents related to the YPS agenda!

The YPSDB provides a comprehensive set of materials relevant to the YPS agenda at international, national, and local levels as well as across thematic issues.

The database includes over 390 unique documents. Accounting for documents available in multiple languages, there are just over 600 documents available in total.

This includes policy documents, research papers, agreements, and other materials from the United Nations, regional organisations, national governments, NGOs, think tanks, youth-serving civil society organisations, youth-led civil society organisations and researchers.

The database is an outcome of my Australian Research Council (ARC) DECRA Fellowship on youth leadership and the YPS agenda, and exists thanks to the fabulous work of the excellent web designer, Daniel Oakley.

During my fellowship, I started collecting relevant documents to analyse for the fellowship project. Over the past years, and through many conversations with others working and researching the YPS agenda, I have realised that such a resource could be of value to others, and I’m delighted to be able to make it publicly accessible with funding from my Fellowship.

Key Features

A quick overview. In providing a comprehensive set of materials relating to the YPS agenda, the YPSDB allows you to:

Search the database online via a friendly online catalogue function

Download a pdf of any of the documents in the database

Access and download the database itself as an excel file for your own use and research (I ask that you cite/acknowledge the origins of the database if you do use it; and I would always love to hear from you about what you do with the resource!)

Filter results by a range of criteria including whether the document is youth-authored or not, what kind of document it is, what region it relates to, or when it was published.

Find documents in multiple languages, when available.

There are some fantastic resources on YPS, such as the youth-led YPS Monitor managed by Mridul Upadhyay. Until recently the youth4peace.info website contained a specific range of mostly institutional documents on YPS; however, in the last month it has been taken down (resulting in dead-links all over the internet I imagine!). The YPSDB also includes links to youth4peace.info—there are 108 links that will now have to be accessed via Wayback Machine; however, the YPSDB contains pdfs of all these documents, ensuring they remain accessible despite other sites going offline.

An important caveat: I know that the database, while comprehensive, is undoubtably missing documents. While I will periodically update it with new documents, I will rely on others to let me know of materials that are missing or recently published. You can do this at any time via a handy suggestion form, and the research team will review these submissions every few months and update the database accordingly. Please help make it the most comprehensive and complete resource to benefit everyone working in this space by submitting relevant resources!

If you want to jump straight in you can visit the YPSDB here: www.ypsdb.org !

What the YPSDB can show us: reflections at the launch

Read on for some reflections on what the database contains, and what it can tell us about aspects of the YPS agenda. These include reflections on the languages of documents, the regional spread of materials, youth-authorship in knowledge production on YPS, how the YPSDB connects related documents and allows users to make connections between the materials, and the known-unknowns: unavailable documents that cannot be included. All the data discussed here comes from the launch version of the database: V1.2.

Languages of the Agenda

For anyone working on and around the YPS agenda, we know there is an overwhelming dominance of English as the functional language of many meetings, events, documents, and reports. There have been some very important (ongoing) conversations amongst advocates about how to expand language and accessibility, especially with limited resources, and this issue needs continued reflection.

So, it is perhaps unsurprising that the documents of the YPSDB reflect this. There are only four documents in the database that do not have an English version; this means 92.58% of the documents are in English. If we exclude the formal records of the UN Security Council and African Union Peace and Security Council (which issue formal documents in all their official languages) that number becomes 100%: i.e., everything else—CSO reports, publications, research and so on—is either only in English or has an English version alongside other language versions.

The database currently includes resources in fifteen different languages. After English, the most common are the official languages of the UN and AU (French, Spanish, Arabic, Portuguese, Russian, and Chinese), but also includes some resources in additional official languages of European organisations like the EU and OSCE (German, Italian, Greek) and a few documents in Finnish, Korean, Sinhala, Swedish, and Tamil.

Figure 2 above shows each of the percentage of documents in each of the six most common languages in total, and then with the UNSC and AUPSC excluded. The presence of Chinese and Russian documents in the UNSC/AUPSC excluded category is due to the presence of some UNGA and other UN documents—there are no unique, non-institutional documents in either of these languages.

All languages decrease when the UNSC and AUPSC documents are excluded, except for English and Spanish. This is interesting and shows that there are a few documents in Spanish from CSOs—particularly during the submissions to inform the Missing Peace, such as #159 and #166 on Colombia, and more recently resources from UNOY including #480 and #489 which is great, given the underrepresentation of the region in the broader agenda (see Figure 3 below for regional spread of documents).

I am very aware the database is likely missing a variety of resources in languages other than English, and this is something I would very much like submissions to help address, especially if they do not exist in English. Expanding the knowledge base of YPS necessarily includes expansion of documentation in other languages. While team members speak Spanish, French, and Portuguese as well as English, we likely have missed documents in other languages. Despite this, I think it is fair to say that the dominance of English in this advocacy space remains a significant feature of the landscape.

Regional Representation

Just like language, there is also regional variation in uptake of and engagement with the agenda, and this is also evidenced in the YPSDB. Documents are tagged with specific regions, or as ‘global’ or (very rarely) ‘N/A’. A document can be tagged in the database with multiple regions.

The above Figure 3 shows the geographical spread of unique documents in the database (excluding those that are ‘global’ or ‘N/A’).

It is evident that Africa as a whole, but especially West and Central Africa (108 unique documents), and the MENA region (106 unique documents), have been enthusiastic adopters of the agenda. Documents that contribute to this include both country-level materials such as those relating to the NAPYPS process in both Nigeria (#185) and the DRC (#256), regional thematic reports (e.g. #491, #255, #491), and is boosted by the formal and sustained engagement with YPS by the African Union (42 unique documents). The African Union is the only regional body that has comprehensively formalised the agenda—including a Continental Framework (#9) on YPS, a 10-year implementation plan (#11) of that framework, and follow up commitments like the Bujumbura Declaration (#25).

Other regions have had less active engagement. Southeast Asia and the Pacific (18 unique documents) has historically been overlooked in YPS activity. ASEAN has been a slower adopter of the agenda, although there have been growing movements and resultant publications in the past few years (e.g. #75 #87, #325). Like many other regions (see Figure 4 above), there is spike of activity in 2017 relating to regional consultations (i.e. #68, #112 (among many others)) and thematic reports (#170, #1, #113 (among many others)), to inform the Missing Peace study.

Youth Authorship

One of the central tenets of the YPS agenda is recognition of the capacity of youth and their inclusion and leadership for the agenda (and peace and security practices more broadly). Efforts to increase youth participation in formal events have been a feature of activity on YPS in the past decade.

However, what does the database show about who is creating knowledge on YPS? Overall, of the total documents, less than 20% are youth-authored or co-authored with adults (see Figure 5). Overwhelmingly, documents in the database are adult-authored (75.8%), while a small percentage are adult-authored but youth were consulted or involved in data collection (4.9%).

When the main institutional documents (which are overwhelmingly adult-authored) are excluded the percentage of youth-authored documents understandably goes up, increasing to 25.8% (see Figure 6). This attests to the range of activity and leadership of youth-led organisations like UNOY, OGIP, and initiatives like the Ally Project and the Journal of YPS, as well as many youth-authored thematic papers submitted to UN processes. There is also a set of Master’s dissertations included here (more on this later).

It is perhaps unsurprising that despite rhetoric on inclusion of youth, their expertise as knowledge producers is less represented in the database. Again, with the caveat of the YPSDB being comprehensive but not complete, there may be documents to be included.

However, I would also hypothesise that the nature of youth-led organisations means their documentation is less likely to be posted online and thus eligible for inclusion, and that this is in part due to the chronic under-resourcing of youth-led peacebuilders—they do so much with what they have, but lack of resourcing can impact both what materials can be produced and how they can be shared. This is something advocates working on YPS can reflect on and address going forward.

Making Connections

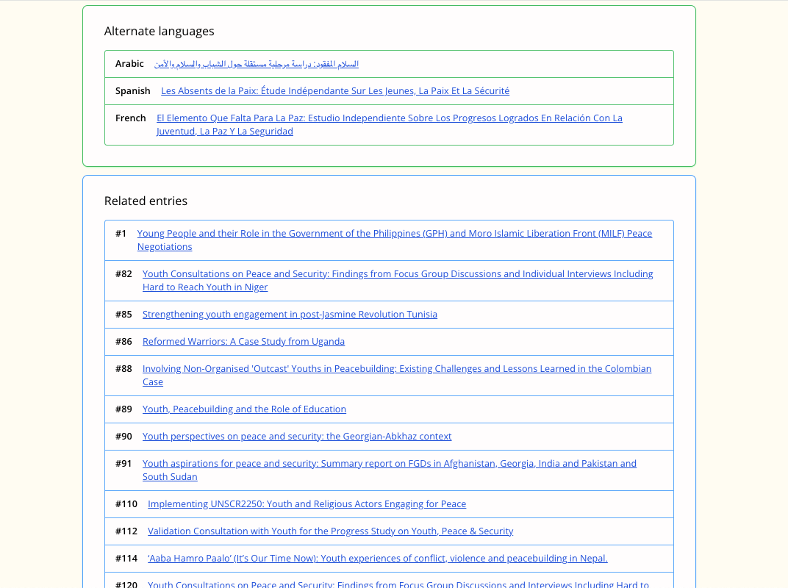

One of the elements of the catalogue I’m very pleased exists is the ‘related documents’ function. In putting together the database, we included a column where documents that were connected could be noted (these refer to different documents, and is separate from the availability of a document in other languages).

A great example of this is the entry for The Missing Peace progress study (#227), to which the team has linked all the documents that informed the study, hyperlinked on the page.

There is a range of these types of linkages across the database. Another example is the Finnish National Action Plan on YPS (#184), which not only is available in three languages itself, but in the ‘related documents’ users can find the youth-led national consultation report that fed into the NAP process (#511, #602, #603).

In both cases, this function helps create connections across the database, but also importantly links the supporting work that youth themselves (alongside youth-serving allies) often do to inform official/formal processes and documents. I hope we can develop and expand this feature as the database grows and can provide more of a ‘story’ of the documents for users, especially for those coming to the agenda in the future who will not know the details of the early years of YPS.

Another means of aggregating entries can be done via the ‘Browse by’ function on the homepage. Users can filter by the kind of document—for example, Formal frameworks, Communication, Resource, or Report.

To take one example here: While users will find a limited amount of academic material in this database, these resources are either cited in one of the official documents like the Missing Peace (#227) or We are Here (#71) reports (ie #83) or are open access (ie. #119, #225 #565). In addition to this, however, the database currently includes thirteen Masters dissertations, currently all youth-authored.

This is the exception to the rule of public availability for submissions to the YPSDB. If it is not available publicly, the author has provided a pdf to be included. I felt this was an important exception given the above discussion on the limited availability of youth-authored materials, and the careful work being done in Master’s programs by practitioner-scholars. If you have written a Master’s (or PhD!) dissertation and would like it included, please reach out.

A note on non-existent records

While the YPSDB is the most comprehensive collection of documents on the YPS agenda, there are still gaps that cannot be filled due to documentation not existing for meetings and events on YPS.

Two examples from the UN in the last year or so:

Last August (2023), Ghana convened a Security Council Arria-formula meeting on “Reinforcing the implementation of the Youth, Peace and Security Agenda for a peaceful and stable Africa”. A concept note (#591) for the event exists, but although it was planned to be live streamed via UNWebTv, it was not. Therefore, there is no record at all of this meeting

This year Mozambique convened a debate on “Maintenance of international peace and security: the role of women and young people”. This was not an Arria-formula event (with the related informality of documentation relating to this format), but a UNSC debate. Again, a concept note (#460) exists; however, there is still no UN document record of it. Statements from some of the Permanent Missions who spoke are available on their own websites, but there is not an aggregated record. I will keep my eye out for this record if and when it becomes available.

I’ve also realised in finalising the YPSDB that sources like the (generally excellent!) Security Council Report, has an out of date and incomplete list of UN Documents for YPS on their website.

These oversights and lack of continuity, and lack of reporting (as well as lack of will to have formal meetings on YPS in the UNSC, but that’s a different complaint!) impact accessibility of information on YPS, demonstrate a lack of commitment to the tenets of the agenda, and helped inform my desire to create a comprehensive and public database for the YPS community and those beyond.

Concluding Comments

I really hope the YPSDB might be a useful resource for others in the YPS community or coming to the space of YPS research and practice. As I’ve written about previously, the engagement of youth in peacebuilding and security extends far beyond the formal policy agenda of ‘YPS’. The YPSDB specifically collates documents that directly relate to the YPS agenda itself. I would strongly encourage people to look beyond the policy parameters of YPS if you are looking for research or policy and advocacy before 2015 on youth-inclusive peacebuilding—this database is limited in historicising this space that we work within. I would also encourage people to look beyond ‘YPS’ since 2015 also; there are some fabulous project, resources, and research on youth-led and youth-inclusive peace and security that continue to be done without reference to the formal agenda.

The YPSDB is comprehensive but not complete. I would very much value your suggestions of missing material or new resources as they are published to build future versions of the YPSDB collaboratively with the community. I would also appreciate knowing about any errors or issues if you come across them. The research team and I have worked hard to make it as correct as possible, but we recognise the potential for imperfections.

I will collate and release updated versions of the database periodically. There are some specific criteria for documents to be considered for inclusion. You can submit suggestions for consideration at any time, but there will be a delay before they are included if they are accepted. You can find more information about the criteria and process for suggestions here.

You can download the excel file of the database at the website here. The purpose of creating this resource library was to make it easier for people to access this information. I hope providing a downloadable file offers opportunities for people to use this information in new and exciting ways that feed back to scholarship and practice on youth inclusive peacebuilding. If you do use the database for publications, reports, commentary pieces or anything else, please let me know! I would also love to include your output on the ‘Publications’ page, which will be a repository of materials that use the YPSDB database.

Enormous thanks and acknowledgements

Finally, I want to end with an enormous thank you those who have helped this project come to fruition. It has definitely been a process that has snowballed in scope and ambition!

I could not have done it without the initial research assistance of Dr Richard Fosu and Hayley Payne, and the more recent research and project assistance of Dr Ingrid Valladares. Enormous thanks to you all. The website would not exist without the cleverness of Daniel Oakley who is responsible for web design and development and has been exceptionally patient and helpful in the process of making the catalogue a reality. Thanks also to my lovely A/Prof Brendan Keogh for moral support and also help with making graphs and wrangling data for some pretty charts.

I am grateful for the funding from the Australian Research Council via my DECRA Fellowship (DE200100937) which enabled the broader research and sustained attention on this research project, and specifically the creation of this website.

Visit the YPSDB here!

The YPSDB was created and is maintained on the unceded lands of the Turrbal, Jagera, and Quandamooka Peoples. We pay our respects to their Elders, past and present and thank them for their ongoing custodianship of Country. Sovereignty was never ceded; this always was, and always will be, Aboriginal land.

Dear All,

Thank you so much for putting together such wonderful and comprehensive content. I really appreciate your efforts, and this provides great insights into my YPS work. You have got a fan here, and thank you again.